or… in search of the dumdeedle

When I was a child I thought everyone had a penis.

Or dumdeedle, as our family called them, a name that indicates

the awkwardness that hung around male sexuality.

Not that I ever saw anyone naked. Except for Junior, my indigenous

foster brother with the unfortunate nickname. He only lived with us for a few

months, but it was long enough for me to know that he had a dumdeedle. I knew,

because we were bathed together, and I remember, because of the time I screamed

in horror, ‘Muuuuum, Junior’s pooed in the bath!!’

I’m told that this misunderstanding is quite common for

young boys. Somehow though I have always felt foolish, about looking at my

newly-born niece being nappy-changed when I was seven, and wondering when her

dumdeedle would emerge from those fleshy folds. Like it would somehow grow out like

a bud emerges from a branch, or turn inside out with a big reveal: Ta-da!

No hope of accidentally discovering the truth about women in

saucy books or magazines lying around the house. Unthinkable in a conservative

Christian family living in Adelaide, the city of churches. And I must have

chosen likeminded friends, as none of them thrust girly magazines under my

delicate unsuspecting nose. The closest I got was a friend’s nudie calendar, the

pose revealing nothing below the waist; I giggled about the dumdeedle the model

was hiding.

There was a dark side to this misnomer, an unspoken fear. In

our family, gentleness was lauded but virility was seen as a threat – a skewed and

unhealthy picture of male sexuality and its power.

I also feel foolish for waiting for something else to appear

that never would. I wouldn’t have called it ‘being straight’ back then. I would

have just called it ‘being like everyone else’.

When did feeling like I belonged with the girls become feeling

attracted to the boys? Who knows? Maybe it was about the time when I stopped

just being fascinated with my own penis (let’s start using the right word), and

became fascinated with penises in general. When I realised that there was not

only something magical about them, there was something magical about those who

possessed them.

Let’s just say that feeling different socially was hard

enough. The pain of feeling different sexually came later.

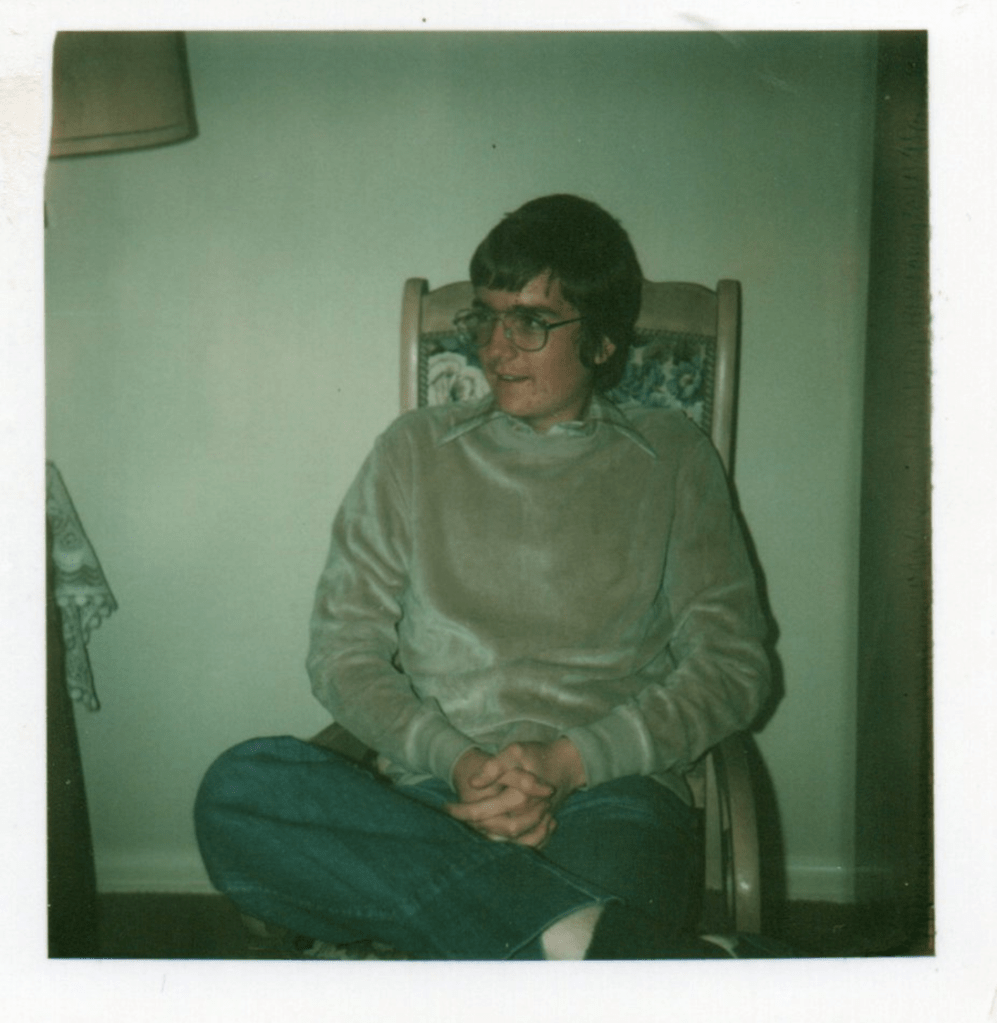

As the youngest of four, with ten years’ gap to my closest

sibling, I was wrapped and indulged in my mother’s love. Apart from the few

years where my parents ran a corner store, she did not work outside the home.

Ladies lunched, and did all the housework, and had dinner on when Daddy came

home. She had the time and the inclination to read to me, to take me ‘to town’

as the city was called, and to make me part of her social circle. Didn’t I love

the attention from her lunch friends, and didn’t I learn how to fit in with

women, and older women in particular. Could have done worse! But the softness

and sensitivity it fostered made the school yard a place that was sometimes

awkward, sometimes hostile.

Cissy. Who uses

that word now? How quaint. Queer, homo, pansy, faggot, poofter – they all stung

at different times along the way. But cissy? From another era.

Neither the girls nor the boys at school knew what to do with

me, for different reasons. The girls would include me in skipping rope until

they tired of tolerating me. And I hated football and cricket and any kind of

contact sport – no let’s be real, any sport – so that ruled out socialising

with the boys. Where I found the girls fickle, I found the boys consistent –

they would have liked to include me, they just found me too foreign.

If I felt like an illegal alien at primary school, then I

felt like a soldier dropped behind enemy lines at secondary school. Box Hill

High School in the 70s had a terrible reputation: an all-boys school that had

long outlived its halcyon days and was known for its skinheads that took

pleasure in flushing the heads of year sevens in the toilet. The advice about

avoiding this fate, given by one teacher, was to try and fit in and not be out

of the ordinary. Paradoxically I found this comforting, though fitting in was

not my strong suit.

Growing up queer, in 1960s and 1970s Australia, meant that

not only did society condemn my orientation; it denied me any kind of role

model, or trope in popular culture. In all those years when I was trying to

figure myself and the rest of the world out, I was told that I was perverted

and wrong and needed to be fixed, but not only that. None of the messages about

what my culture valued, in terms of love and attraction, reflected who I loved

or felt attracted to. The cultural mirrors of TV and radio portrayed ‘boy meets

girl’, ‘boy loses girl’, ‘boy wants girl to jump in his car’, ad nauseum. It seems like a logical

set-up – two sides of the one coin – but in reality, if felt like a sharp

‘one-two’ punch.

The prevailing orthodoxy was that being gay was an illness. It

said so in medical manuals, acts of parliament, sermon notes and broadsheets. It

pained me greatly – that the only porn I was interested in at our local

newsagent was Loving Couples: hetero but including men. That my dreams featured

surprise cameos of strong and decent classmates that I didn’t realised I

fancied. That it was the fathers of

friends that made me weak at the knees.

How does a young person work out who they want to be without

role models? Or without hearing and seeing themselves in the music and movies

they consume? Today we have lesbian talk-show hosts, gay cinema, and Queer Eye.

Then it was all homogenous and heteronormative. Mind you, popular culture was

more monolithic then and your diet was very restricted – everyone watched the

same music shows and listened to the same radio stations. But even Ian ‘Molly’

Meldrum, the camp host of the universally watched Countdown, was still in the closet, and a young gay boy in suburban

bible-belt Blackburn was all at sea.

To be fair, there were weak signals, emerging in culture,

that I could have picked up if I was willing. One book in our school library

had a picture of two men in the bath (Young

Gay and Proud?) and I remember being repulsed by it. Self-loathing and

internalised homophobia are very powerful. And there were more liberal

publications I liked to peruse at the library, like Films and Filming, which might occasionally have a feature on soft

core homoerotica like Sebastiane. I

was never brave enough to see that film, but my late friend Stephen was.

Stephen and I had an unusual friendship, then and later. He died

at 50 without ever coming out – once even explicitly denying being gay in a rare

moment of candour – but all who knew him were convinced he was. As teenagers we

both had an interest in art and design, and would spend weekends visiting

architect-designed display homes together. There was nothing romantic – at

least I never picked it up – nor sexual. He introduced me to GQ, not BEAR. But we had an unspoken parallel fascination with men. Like the time we happened upon a gay bookshop

in Chinatown and we both stood transfixed outside, looking mutely at a copy of Lusty Lads in the display case, lumps in

our throats and pants.

My high school peers were not so mute. They knew what was

going on with me. I got names and slurs and cut-outs of money shots shoved in

my locker.

At least I was not driven from the school like one

unfortunate teacher.

I say unfortunate because he appeared to have been tried in

the kangaroo court of uneducated schoolboy gossip. The whispers in the

quadrangle were that he was ‘… under suspicion… you know… of being a homosexual’. How dreadful. The whispers

that came soon after were that he was ‘into little boys’. Sadly, in his case, I

think both were probably true. In those days, many people equated homosexuality

with paedophilia; I fear there are still some now who do. We now know that

paedophiles are most strongly attracted to minors, and only secondarily to a

particular gender – not always their own. Undoubtedly this man should never have

been a teacher – I don’t at all want to minimise the inappropriateness of his

presence at the school. However, something striking stays with me, something inconceivable

in the era of the hugely significant Royal Commission into child abuse, and the

national vote on same-sex marriage. In the 70s the implied shame around him

being a poof was even worse than that of being a paedophile.

My sense of feeling different to my peers grew at high

school. Not only was I feeling the urges, desires and preoccupations that

accompany puberty, completely disrupting the emotional status quo of childhood.

I was having them in a way that was totally unacceptable. I was on the same

testosterone-fuelled roller coaster as my schoolmates, but they were enjoying

themselves and I was screaming for it to stop. I simultaneously loathed them, and

desired them for their machismo, but above all I envied them because their

experience was ‘normal’.

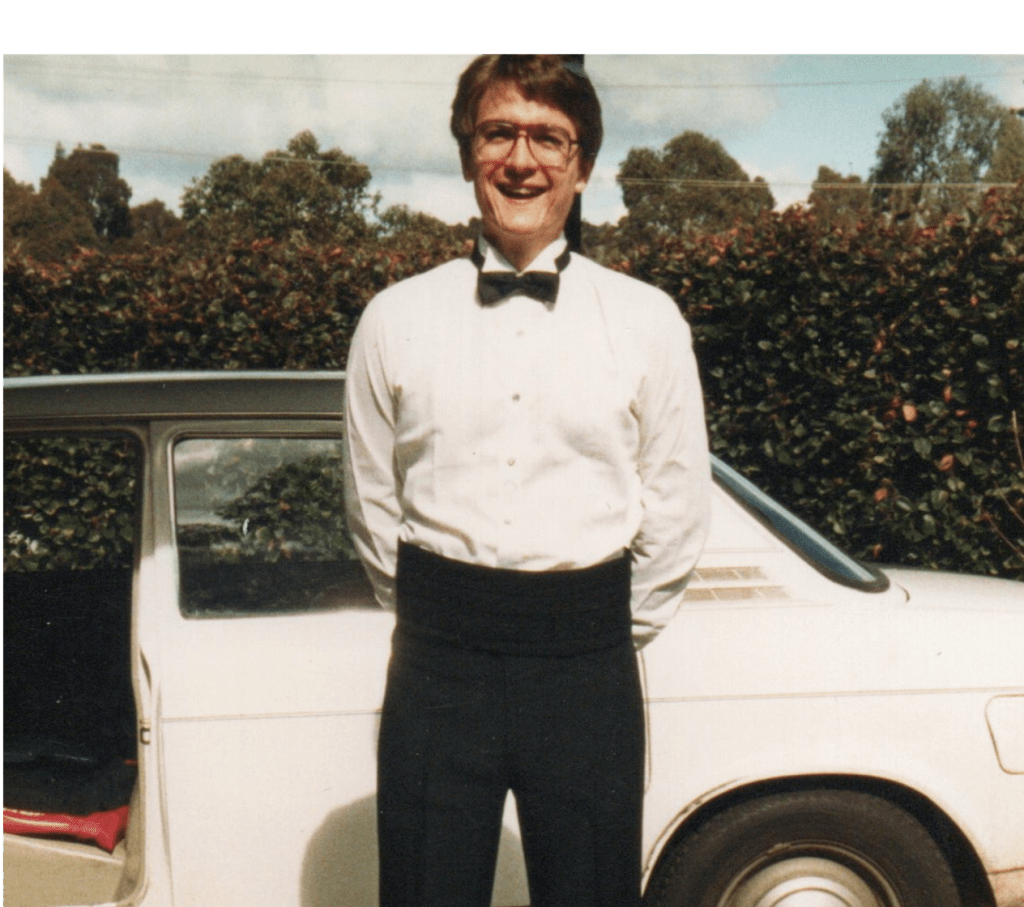

There was some relief in years eleven and twelve, at least

socially, when I felt like my peers grew up and my sense of otherness

diminished. I found the pubescent sexual energy around me tantalising, yet I

was really not attracted to brashness or roughness. I was drawn to the

tenderness that I saw in romance, and fatherhood. I was ashamed of it at the

time, but now I don’t care that I crave the strength and tenderness of men. In

my youth I was fascinated with men being loving and attentive with their wives

and children, and I was embarrassed about how I couldn’t stop staring at that

young dad at church.

What I could stop, and in fact never started, was acting on

my feelings. That began in puberty and lasted for decades. In my dour Scottish

and Cornish heritage, permission-giving and self-compassion were in short

supply. I have always been the master of keeping a tight lid on it. Gay men are

typecast as horny and profligate. I have realised that while I enjoy a normal

libido, I am curiously chaste.

Permission-giving is the reason why popular culture is so

important. The absence of visible healthy same-sex relationships condemned my

orientation, as loudly as any sermon. Being such an upstanding and moral

household, we never watched Number 96,

the breakthrough soap opera that brought the sexual revolution into Australian

lounge rooms. I was unaware of the early depictions of gay men on Australian

television. The assumption about being a homosexual man was that it was a dark

and lonely life, without the sunshine of children or stable domesticity.

Which partly explains a poignant sub plot to my narrative. When

I was 18, the older brother that I had idolised growing up came out as gay. He

was 30, had never had a serious girlfriend, and read books like The Church and the Healthy Homosexual. But

I had never cottoned on that he might be same-sex attracted. There are none so

blind. Society, my family, and I were not ready in 1980 to embrace his way of

being. Rather than seeing it as the role model I longed for, I perversely doubled

down on my internalised homophobia, turning in on myself, like a pot-bound

plant.

As I think now about the fact that my dear brother was gay

and out, and yet I could not follow in his footsteps, it feels ludicrous at

first reading. But remember in 1984, at Wham!’s

zenith, George Michael could not come out for fear of sabotaging his pop

career. It was the bravest of the brave who went there, and I recognise that

today I stand on the shoulders of giants like my brother. We now get on well,

but for a long time he kept family at arm’s length. I did not get a sense that

he saw himself as a role model, and I’ve never asked him whether he suspected I

was gay. I guess he took my assertions of straightness at face value. When I told him much later of being same-sex

attracted, his somewhat disappointed rejoinder was that he thought he was the

only gay in the village! Thank you, Little

Britain.

As a young person there was not a snowflake’s chance that I

could have formed a romantic or sexual relationship with a boy. I had a couple

of crushes on girls in my high school years but I’m sure they both thought I

was just plain weird. Again, maybe they knew. I joined a conservative Christian

group at uni that pedalled a puritanical and patriarchal view of relationships.

I met a woman with whom I later fell in love, and who agreed that I could pray

away my gay. A few years later I married at 22 and was on my way to having a

family.

I had grown up (or thought I had), and despite my best

efforts, grown up queer. But that is only half the story. I still had to do a

lot of growing into my queerness.

First, I had to stop fighting it. I fought it for all of my

20s. At 24 I joined another conservative Christian organisation that actively

promoted the idea that I could be ‘healed’ from the sin of homosexuality. This

practice is known now as reparative therapy, but there is nothing repairing or

therapeutic about it. It is harmful and abusive.

I endured lectures, prayer ministry and exorcisms. I tried

to control my thought life, embrace the ‘father heart of God’, and resist the

demons of same-sex attraction. I was told to believe in the transforming power

of Christ, seek healing for childhood trauma, and stand up straight and stick

my chest out – subtext: like a real man.

Where are those conservatives now, who told me to choose

between my orientation and my faith? I hear that some of them still peddle this

lie. Integrating sexuality and faith is now as seamless to me as integrating

eye colour and faith – it is just a non-issue. In my experience, orientation

and faith both evolve and develop over time, coming to deeper truth. How I have

identified sexually has evolved from ‘gay and happy in a straight

relationship’, to ‘bisexual’, to ‘gay’. How I have identified in faith has

evolved from Christian to maybe ‘post-Christian’. I have journeyed beyond the

faith of my forebears into a deeper experience of my own spirituality, and incorporated

truths I have discovered from other faiths. I’ve sought to replace the verbiage,

noisiness and activity of my Christian tradition with the consciousness, awareness

and silence of others. I think it’s

incredibly lucky that I have kept a faith considering what I put myself

through, and what others put me through.

I did all this willingly. Being healed was what I wanted. I felt

guilty that my eyes always lighted on men when I walked down the street, and

not women like they were supposed to. I devoured books and tapes that proposed

psychological explanations and psychological cures: how to make up for supposedly

unmet needs in childhood and allow God to effectively ‘re-parent’ me.

Eventually I tired of that endeavour and begrudgingly came

to the conclusion that this thing was here to stay. I was able to maintain a

healthy sexual relationship in my marriage, and my orientation was not the main

thing I felt I needed to focus on. Whenever I semi-consciously asked myself how

I was able to have a fulfilling sex life, I shied away from digging too deep.

Sex was a positive thing in my relationship; I worried that if I tried to

consciously reconcile that with being gay, I would undermine its potency and

comfort. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

Into my 30s, I gradually came to embrace my same-sex attraction

as part of who I was. In my 40s I gradually came to enjoy it. Not that I acted

on it, save for the occasional trip to a gay sex shop just to be in the zone.

And even then I did not allow myself any kind of fantasy life. I equated that

with acting out my desires; I was fearful that either might let the genie out

of the bottle.

I felt both in and out of the closet. I had had a long

succession of comings-out, starting young. I had come out to my wife-to-be,

before we were even engaged, when I told her that I thought I was gay. I had

come out to my spiritual ‘leaders’ (!) when I asked them to pray for my healing

from homosexuality. And throughout my adult years, as I formed new friendships

and felt I could trust people, I came out to them too. My straight male friends

– all my friends really – were an important part of my coping and living well with

my situation: gay, and married with a growing family.

Many people suspected of course and some saw through it all,

but with compassion. Like when I attended the 25-year high school reunion. It was

an illuminating experience to be with the boys-to-men with whom I had spent six

years. We had nothing to prove to each other. We had seen the best and the

worst of each other and there was a remarkable ease, even though we had not

seen each other for decades. Their take on my sexuality? ‘You have six kids

now? Wow, at school we all thought you were gay!’ Said without rancour or bile.

In my 40s I had a mid-life crisis, lost weight, got a tattoo

and started working out. I knew even then – consciously – that my attention to

my physical appearance was about being attractive to other men. I had no one in

particular I was trying to impress. I’m not quite sure what I thought the

end-game might be. Maybe it was an important step of integrating all the parts

of my life – having my external self align with my internal self. But my drive

to be fit and buff was almost unstoppable. In 2011 I had a major shoulder injury,

but I was not dissuaded. I endured months of rehab in order to get back to full

fitness. In 2014 I even did a photobook of artsy muscle shots with a

professional photographer friend. The energy of the sublimated drive of my

sexuality was immense.

Into my 50s the sense of pain became overwhelming: the life

I had chosen, and loved, was preventing me from fulfilling my deepest desires.

I thought that my heart would break if I could not be with a man. At 51 I

became mentally unwell due to it, depressed then manic. I somehow managed to pull

through it and keep on living as I was, but something had shifted without me

realising. I began to allow myself a fantasy life. I started to identify as

bisexual, and came out as such to my colleagues and adult children. And I

joined GAMMA – Gay and Married Men’s Association – a peer support group for

bisexual men.

GAMMA was both helpful and tough. It was helpful to be able

to share my story, have it validated, and hear about how other men navigated

being same-sex attracted while in a straight relationship. It was tough because

it laid my plight bare: I had a wife whom I cared about deeply and who trusted me;

and all around me were stories of the urge and drive to have sex with men. It

seemed universally potent and, contrary to how I was living at the time,

virtually undeniable long term. It was like one tectonic plate pushing into

another, the pressure building and building.

The quake came when I changed therapists on my wife’s

insistence regarding other issues in our marriage. Through learning compassion

for self and a fresh perspective on my marriage, the balance tipped: the forces

pulling me out of the relationship became greater than the forces holding me in.

After 31 years it was all over.

I take responsibility for entering a marriage where the very

foundation was flawed. Yes, there was great love there, but there was a massive

lump under the carpet.

And I have compassion for myself. In my Australia there was

no room to grow up queer in society, culture or church.

Coming out at the dissolution of my marriage was a massive

relief. My outsides finally matched my insides and I could live an integrated

life. I told anyone who cared to listen. I spoke publicly about my story to a

couple of hundred people at my workplace for IDAHOBIT. As a result, I was

invited to speak at a motivational event. And in doing publicity for that event

I was able to speak on radio, including the ABC, the Australian public

broadcaster. People still tell me randomly that they heard me that day.

I continued to grow into my queerness. Once GAMMA closed up

due to lack of government funding, I started seeing a man I had met there, who became

my partner. Yes, I found love. With him, and on my own, I have explored and

discovered the gay Melbourne scene. At least some aspects of it, because the

scene is huge. In doing so I have explored and discovered that I am quite

chaste, as I said before. But to not only visit Sircuit, DTs, The Greyhound,

The Laird, Mannhaus, The Peel, Club 80 and other venues – to see them as ‘my

hood’ and ‘my tribe’ – is a joy and a privilege.

And while these things have been thrilling, nothing compares

with being with my partner. Being with him, and finally being able to act on my

feelings, has been like coming home. Whether the days have been bucolic –

dancing and bar-crawling our way through the inner-urban enclaves of Balaclava

and St Kilda – or lean – rebuilding relationships with my children, or living

in separate states while he and I sorted our respective lives out – they have

been dear to my heart. And when I am in his arms, fifty years’ worth of dreams

have finally come true.

When did those dreams start? In my own heart, yes, but also

through reappropriating the popular culture and advertising of my youth. I

clearly remember a TV ad for jeans in the racy 70s. Yes, it was actually pretty

liberal then – the sexual revolution, the cutting edge of nudity in film, like

the Alvin Purple movies, and the

heady days of socially progressive prime minister Gough Whitlam. The TV jeans ad

in question ends with this hairy chested hunk sitting up in bed expectantly,

with his pants draped artfully in the foreground. While curvaceous young women

occupied the rest of the 30 seconds, I knew that I wanted to accept his unspoken invitation at the end.

So, in my formative years, did I find anyone in music or film to model myself on? A few: the rare breed

of caring men that later became known as Sensitive New Age Guys – who were

interested in treating women well, and not as objects. Who talked about their

feelings, and were keen to please their female partners. I could never

understand how men could treat women as targets of raw lust and desire, without

reference to who they were as whole people.

That is until, as a 53 year old who had grown up queer and finally

grown into his queerness, I saw the Boylesque

floorshow at the Greyhound Hotel, the now defunct venue flaunting all things

youthful, gay and sexy. Acres of young male flesh, sweating, strutting and gyrating.

Didn’t I hoot and holler? Didn’t I abandon all decorum? And I finally understood

what my straight male counterparts had been doing all those years, and why.

I finally saw in myself the unabashed, unashamed and

uncensored desire I had seen in my school mates, and men ever since. I had come

to love and enjoy my male sexuality, and my homosexuality. I had embraced both

gentleness and virility.

I had traded in the dumdeedle.

I had found the penis.